1936-1999: “The Nucleus of an Art Movement”

As we consider AAA in the 20th Century, we look to Esphyr Slobodkina to deepen the story. “When, finally, in 1936, the Museum of Modern Art did offer its public an exhibition of cubist and abstract art, only European artists were included. The abstract artists did exist in America, but the contact with [their] public was all but entirely denied [them].

“It was to face these problems that a group of painters and sculptors working, in varying degrees, in the non-objective form of art, began to meet at [Ibram] Lassaw’s studio. These meetings were limited to the most militant few. Theoretical and practical sides of artists’ problems came in for a considerable amount of heated discussion. So much so that the news of a new and exciting prospect of forming a nucleus of an “art movement” spread rapidly, and other painters and sculptors working in non-objective or near non-objective form began to join the informal meetings.”

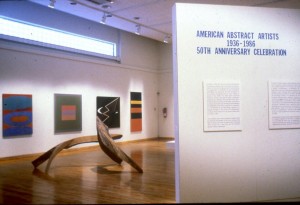

In the catalog American Abstract Artists, 1936-1986: 50th Anniversary Celebration, a chronology compiled by Philip Verre and Ward Jackson, with assistance from Leo Rabkin, Irene Rousseau, Merrill Wagner and Slobodkina, we learn the salient aspects of the group’s history. In January 1936 preliminary discussion took place to consider establishing a group of abstract artists, and meetings would continue throughout the year. On January 8, 1937, the group decided to call itself the American Abstract Artists. The group’s first exhibition took place in April of that year. There would be annual exhibitions, some traveling, at commercial galleries, academic galleries, and museums for the next 50 years—as well as talks and panel discussions—a tradition that continues today.

“On April 3, 1937, the first exhibition of American Abstract Artists opened at the Squibb Gallery, 57th Street and Fifth Avenue. While the reception by the press was far from favorable, the enormous attendance of over 1500 visitors during the exhibition period showed the genuine interest this unconventional art movement could count upon.”

– Esphyr Slobodkina

Read more: AAA Historical Outline by Esphyr Slobodkina

“Burgoyne Diller, who at the time [1936] was [Project Supervisor] of the WPA Mural Division in New York [City] became the group’s leader and was able to employ a number of these modernists in his program. A.E. Gallatin was an early ardent supporter of American modernists. At his Gallery of Living Art at New York University he exhibited many of AAA’s works, wrote about them and contributed to their cause.

– Franz Geierhaas

Read more: Journal of the Print World

Other founding members included Josef Albers, Ilya Bolotowsky, Balcomb Greene, Gertrude Greene, Alice Trumbull Mason, Ray Kaiser (later Eames), George McNeill and Vaclav Vylacil, a total of 39 artists, most based in New York City. In subsequent years they would be joined by such artists as Alice Adams, Richard Anuskiewicz, Will Barnet, Perle Fine, Suzy Frelinghhuysen, Marcia Hafif, Ward Jackson, Vincent Longo, Judith Murray, Lucio Pozzi, Dorothea Rockburne, Judith Rothschild, and Merrill Wagner.

What Slobodkina called “the non-objective form of art” was defined and explained by AAA members in their own essays. “The artist no longer feels that he is “representing reality. He is actually making reality,” wrote Ibram Lassaw in “On Inventing Our Own Art,” first published in American Abstract Artists 1938 Yearbook

Read more Two Essays by Ibram Lassaw

Hans Hoffman, from an address he delivered at AAA’s Fifth Annual Exhibition in 1941, declared:

“The mutual dependency of form and color has a Life of its own—it is pictorial Life. A painting that does not fulfill this aesthetic necessity is rather everything else but painting. Modern art differs from the art of the past in its conception as well as in its means of execution. The artist of the past copied physical Life and used arms and legs and heads as means to give his work the appearance of Life. The modern artist uses the elements of construction to create pictorial reality: he creates pictorial Life.”

Read more: Hans Hofmann’s Address

Ward Jackson, who chronicled the history of AAA, reflected on the entry of Piet Mondrian, who joined AAA in January 1941 after fleeing Europe in advance of the War:

“Mondrian shows his painting New York with the AAA in its annual exhibition held from 6 to 23 February . . .1941 at the Riverside Museum. New York, Mondrian’s first painting since arriving, was composed entirely of black lines. In its second state as Boogie Woogie, New York, 1941 – 42 he adds the red lines and blue and yellow planes.”

Read more: Mondrian and The American Abstract Artists

Jackson noted that even before Mondrian’s arrival, which was facilitated by AAA member Harry Holtzman, the painter had “had an impact on members.” And yet AAA would in turn have an impact on American abstraction.

“This organization’s oft-recounted origins . . . can be considered pivotal to a concentrated emphasis on abstract art in this county, to the evolution of New York City as a center for art, and to the recognition of American art on a par with that of Europe.”

– Judy Collischan Van Wagner in the catalog essay for the group’s 50th anniversary.

Source: American Abstract Artists,1936-1986: 50th Anniversary Celebration

In the same publication, Philip Verre, then chief curator at the Bronx Museum of the Arts, wrote:

“The late forties and early fifties are marked by the group’s effort to disseminate [abstraction] on an international level. The first foreign tour of AAA works took place in 1950 with presentations in Paris, Copenhagen, Rome and Munich. An exhibition in Tokyo’s Museum of Modern Art was organized in 1955. The AAA also arranged for abstract artists from other countries to show with the group in America . . .Activities of this type culminated in the 1957 AAA publication, The World of Abstract Art [which is] to this date not only a major research tool but a seminal art document of the 1950s.”

Robert Storr brings us into the ensuing decades:

“The 1960s and 1970s witnessed the rise of Hard Edge and Minimal art but the need for dialogue with artists not aligned with those styles remained. AAA Filled it. During the long drawn out pluralist era that has followed, tendencies competing for brief dominance have come and gone, but steady, slow-moving currents that crisscross and occasionally blend with the ‘mainstream’ still seek places to pool and grow. For many who have been affiliated with it . . . AAA has been and remains such a basin.”