Blurring Boundaries:

The Women Of AAA,

1936–present

Curated by Rebecca DiGiovanna

Clara M. Eagle Gallery, Murray State University, Murray, Kentucky, September 27 – November 1, 2018

Ewing Gallery, University of Tennessee at Knoxville, Knoxville, Tennessee, November 15 – December 10, 2018

Warner Gallery, South Bend Museum of Art, South Bend, Indiana,

October 17, 2020 – January 3, 2021

Blurring Boundaries:

The Women Of AAA, 1936–present

Curated by Rebecca DiGiovanna

“The stamp of modern art is clarity: clarity of color, clarity of forms and of composition, clarity of determined dynamic rhythm, in a determined space. Since figuration often veils, obscures or entirely negates purity of plastic expression, the destruction of the particular form for the universal one becomes a prime prerequisite.”1

– Perle Fine (1905-1988)

Perle Fine’s declaration for the hierarchy of distilled form, immaculate line, and pure color came close to being the mantra of the 1930s and of American Abstract Artists (AAA). Founded during the disorder of Great Depression America, AAA was established at a time when museums and galleries were still conservative in their exhibition offerings. With its challenging imagery and elusive meaning, abstraction was often presented as “not American” because of its derivation from the European avant-garde. Consequently, American abstract artists received little interest from museum and gallery owners. Even the Museum of Modern Art, which mounted its first major exhibition of abstract art in 1936, hesitated to recognize American artists working within the vein of abstraction. MoMA’s exhibition, Cubism and Abstract Art, at the time groundbreaking for its non-representational content, filled four floors with artwork, largely by Europeans.2 This lack of recognition from MoMA angered abstract artists working in New York and was the impetus behind the founding of American Abstract Artists later that year.

In the early 1930s, abstract artists flocked to a new school founded by the German artist Hans Hofmann. For young artists, Hofmann’s class nourished a pioneering interest to learn the techniques of the European modernists. Included in his eager group of ready-admirers were artists Nell Blaine, Lenore [Lee] Krasner, Ray Kaiser [Eames], Perle Fine, and Mercedes Carles [Matter]. Although Hofmann was more welcoming to women than his contemporaries, he was still partial to male artists, once telling Lee Krasner that her work was “so good you would not believe it was done by a woman.”3 Perle Fine recalled a day when Hofmann, bitter and frustrated as more of his male students left to enter military service, pointed to each woman in his class and declared “You’ll amount to nothing. You’ll amount to nothing. You’ll never get anywhere. You’ll never get anywhere.”4 Despite Hofmann’s criticisms, the women who attended his school during the late 1930s and early 1940s considered the experience a formative one, as it gave them an opportunity to gather and discuss their ideas and work. Hofmann’s school provided a place to establish friendships and community, spawning a new generation of likeinded artists who eventually transitioned from student peers to AAA members.

In 1943, several of AAA’s female members participated in an all-women’s show, entitled 31 Women, at Peggy Guggenheim’s Art of This Century gallery. Critical reception of 31 Women echoed the patriarchal sentiments expressed by Hofmann and common at the time. New York Times reviewer and senior art critic Edward Alden Jewell declared that, “the work might just as well have been produced by ‘The Men’”5, while an anonymous reviewer in ArtNews asserted, “the works…[promote a] new conception of the weaker sex. Other all-female organizations should have a look-in at a show which is so refreshingly un-ladylike.”6 Time magazine critic James Stern refused to write about the show altogether, proclaiming that women should simply stick to creating with their bodies.7 Peggy Guggenheim, herself indifferent to women artists, scheduled the show’s opening the month before the gallery closed for the summer; a date she considered inconsequential as the potential audience flocked elsewhere to escape the summer heat.8 The art world had room for models and mistresses, but not for women artists in their own right. Women who were married to successful artists, critics, or collectors were slightly more visible, but in general, women artists stood a strong chance of being undervalued or ignored. To avoid dismissal simply on the basis of gender, many female artists used only surnames or initialed their canvases. Lenore Krasner changed her name to the androgynous Lee, while Irene Rice Pereira simply used the initial I. Whereas subject matter could be problematic for women painters—conjuring images of pastel flowers or beatific children—in abstraction, the gender of the painter made little difference. Absent gender specific signifiers, pure abstraction gave women a freedom they did not have when painting representationally. By the time of Guggenheim’s second women’s show, a 1945 exhibition entitled The Women, perceptions regarding women within abstract art were shifting, but critical review was still tinged with surprise at their ability to create strong abstract work.

If the reception of women in Guggenheim’s shows could be described as dismissive at best, the opposite was true of their participation within American Abstract Artists. From the outset, both as women and as abstract artists, women of AAA were working on the periphery of the art world. Perhaps as a result of their mutual status as internal exiles of the art world, both male and female members of AAA established goals which included advocating for abstract art and the inclusion of all abstract artists in museums and galleries. In comparison to the other abstract artist collectives of the period, where equal footing for women was unusual, AAA provided a place of refuge for female artists. Women within AAA have enjoyed a remarkably active history and generative role since the group’s founding and have been instrumental in articulating its mission within the arts community. Founding member Gertrude Greene coordinated the group’s first exhibitions, including the opening group show at Squibb Gallery in 1937.9 Esphyr Slobodkina, another of the group’s founding members, was also the organization’s first secretary, later serving as president, treasurer, and bibliographer. Among the thirty-nine founding members of AAA, nine were women. Of the group’s fifteen presidents, six have been female. This gender mix was highly unusual at the time. Still today, the group’s membership, a nearly even divide between men and women, remains remarkable within the broader art world.

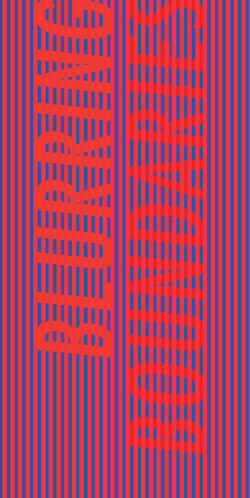

More than 80 years after its founding, AAA continues to nurture and support a vibrant community of artists with diverse identities and approaches to abstraction. In celebration of this tradition, Blurring Boundaries: The Women of American Abstract Artists traces the work of the female artists within AAA from the founders to contemporary, practicing members. Included are works by historic members Perle Fine, Esphyr Slobodkina, Charmion von Wiegand, Irene Rice Pereira, Alice Trumbull Mason, and Gertrude Greene, as well as works by current members, such as Ce Roser, Irene Rousseau, Judith Murray, Alice Adams, Merrill Wagner and Katinka Mann. Through fifty-four works, the exhibition explores the stylistic variations and individual approaches to guiding principles of abstraction: color, space, light, material and process. In Lorenza Sannai’s geometric, hard-edged painting, Ordine Sparso, interest resides in the rigor of straight line, shape, and formal composition. Both Gertrude Greene and Laurie Fendrich imbue geometric shape with biomorphic qualities: Greene’s Related Forms suggests interaction between two totem-like bodies; Fendrich’s anthropomorphic, angular figures are rooted in familiar forms of popular comic characters, like Charles Schulz’s Peanuts series. In Esphyr Slobodkina’s reductive gouache, The Red L Abstraction, intersecting shapes take on the mechanical structuring of a Constructivist blueprint. Patricia Zarate’s Sweet Spot and Siri Berg’s Bars are characterized by pattern, precise and controlled application of pigment, and unmodulated color.

Several artists explore seriality, combining and re-combining vertical or horizontal bands of color as they work out formal problems of space and light. In Gabriele Evertz’s Toward Light, Evertz subtly shifts from bars of achromatic grey to bands of bright white, visually coaxing viewer’s gaze from edge to edge. Emily Berger’s and Kim Uchiyama’s works share an engagement with horizontal line, but with distinctly different outcomes. Uchiyama’s Archaeo stacks pure colored bands in dense, stratigraphic layers, while Berger’s Breathe In transforms airy, dry-brushed marks into mindful exercises, each band swelling across the canvas in a visual inhale. Careful compositions and geometric arrangements are juxtaposed with works which employ more immediate, intuitive forms of expression. Here, much of the emphasis is on the material nature of painting, as artists like Claire Seidl and Iona Kleinhaut use broad, bodily strokes or repetitive, painterly marks to evoke internal emotion and thought. In Laughter and Forgetting, Cecily Kahn fragments color into a kaleidoscope of frenzied marks, compactly mapped in a boisterous landscape. Anne Russinof’s Inside Out evokes pleasure in the recorded gestures of the body, as sweeping, arching movements spread with bright blooms of color across the canvas.

Many of the artists find inspiration for their work in a variety of materials and everyday objects. Gail Gregg’s Scored uses scavenged cardboard, replete with corrugated lines and layered in encaustic; Phillis Ideal unites collaged elements with layers of spray paint, acrylic, and resin in Borrowed Blue; Susan Smith mingles watercolor and graphite with found French fry containers; and Melissa Staiger supplants canvas for subway tiles in Connection 2 Ways. Lynne Harlow situates the viewer among hanging strips of vinyl to create an intimate, light-filled space in Sweetheart of the Rodeo. Mary Schiliro suspends translucent strips of mylar from clothespins in an exploration of color and light in Drip-dry. Silastic resin, masking tape, and sand casts also make an appearance alongside painted shaped canvas and wood, works on paper and Yupo, and digital animation. Both Raquel Rabinovich and Vera Vasek engage bodies of water as co-creators. Vasek employs the ocean tide to cast large-scale movement drawings in August 24, 2007. In Rabinovich’s River Library series, mud becomes metaphor for language as it traces the ancient story of the Nile river from which it is collected. Beatrice Riese and Jane Logemann use written language as medium in their work; in Plum-Korean, Logemann replicates the word for plum over and over, the painting becoming a concrete poem in the color plum; in Riese’s Kufa, densely-gridded glyphs are stitched together to create a quasi-alphabetical design of pattern and text.

In an overdue celebration of this intergenerational group of artists, Blurring Boundaries highlights the ways in which the women of AAA have shifted and shaped the frontiers of American abstraction for more than eighty years. The exhibition emphasizes a variety of approaches, materials and processes within a shared visual and conceptual vocabulary; each work enters into a conversation with the others. What emerges from Blurring Boundaries is the organic, ever-evolving nature of abstraction as a language centered upon the dynamic synthesis of line and form, mark-making, color, space, and light—a language impossible to articulate through the boundaries and stereotypes of a gendered lens.

—Rebecca DiGiovanna, curator

1 Kathleen Housley, Tranquil Power: The Art and Life of Perle Fine, (New York: Midmarch Arts Press, 2005), 100.

2 Museum of Modern Art. Cubism and Abstract Art. The Museum of Modern Art, 1936, https://www.moma.org/documents/moma_catalogue_2748_300086869.pdf

3 Randy Rosen and Catherine C. Brawer, Making their Mark: Women Artists Move Into the Mainstream, 1970-85 (New York: Abbeville Press, 1991), 30.

4 Miriam Schapiro, Art: A Woman’s Sensibility (California: California Institute of the Arts, 1975), 20.

5 Edward Alden Jewell, 31 Women Artists Show Their Work, The New York Times, 6 Jan. 1943, https://www.nytimes.com/1943/01/06/archives/31-women-artists-show-their-work-peggy-guggenheim-museum-offers.html.

6 Helen Langa and Paula Wisotzki. American Women Artists, 1935-1970: Gender, Culture, and Politics (England: Ashgate Publishing, 2016), 36.

7 Alexander Russo, Profiles of Women Artists (Frederick, MD: University Press of America, 1985), 133.

8 Ibid., 133.

9 Joan Marter, Women of Abstract Expression (England: Yale University Press, 2016), 179.